Incandescent bulbs were supposed to be relics, pushed aside by compact fluorescents and then by ultra-efficient LEDs. Instead, they are quietly reappearing in homes, on holiday displays, and in online shopping carts for reasons that have more to do with health, aesthetics, and control than with retro sentimentality. The comeback is uneven and often niche, but it is real enough that regulators, manufacturers, and consumers are all being forced to rethink what “better” light actually means.

Behind the soft glow is a harder story about market power, sensory comfort, and the limits of efficiency-only thinking. As people spend longer hours under artificial light, they are discovering that not all lumens feel the same, and that the cheapest watt is not always the one they want over a dining table or a child’s desk. Incandescent technology, written off as wasteful, is being reframed as a premium option in a lighting ecosystem that is finally big enough to accommodate more than one winner.

The quiet revolt against harsh efficiency

The modern lighting market was built on a simple promise: use less energy, save money, and help the planet. LEDs delivered on that bargain, but they also introduced new frustrations, from flicker and color cast to complex dimming behavior that many people never quite learned to love. As a result, a subset of consumers is now treating incandescent bulbs as a kind of corrective, a way to reclaim control over the quality of light in their homes. Advocates argue that the shift is not about turning back the clock, but about restoring choice in a market that had become dominated by a single technology.

Some of the most vocal defenders frame this as a “Win for Market Competition and Your Health,” arguing that the warm, continuous spectrum of incandescent light can feel less jarring than the spiky output of some LEDs, especially for people sensitive to flicker or blue light. In that view, the renewed demand for traditional bulbs is a rational response to lived experience, not a quirk of nostalgia, and it is helping keep pressure on manufacturers to improve the comfort and color quality of newer products as well. That argument is central to pieces like Why Incandescent Bulbs Are Making, which explicitly links consumer health concerns to the case for keeping older technologies available.

Light quality, mood, and the case for “wasteful” bulbs

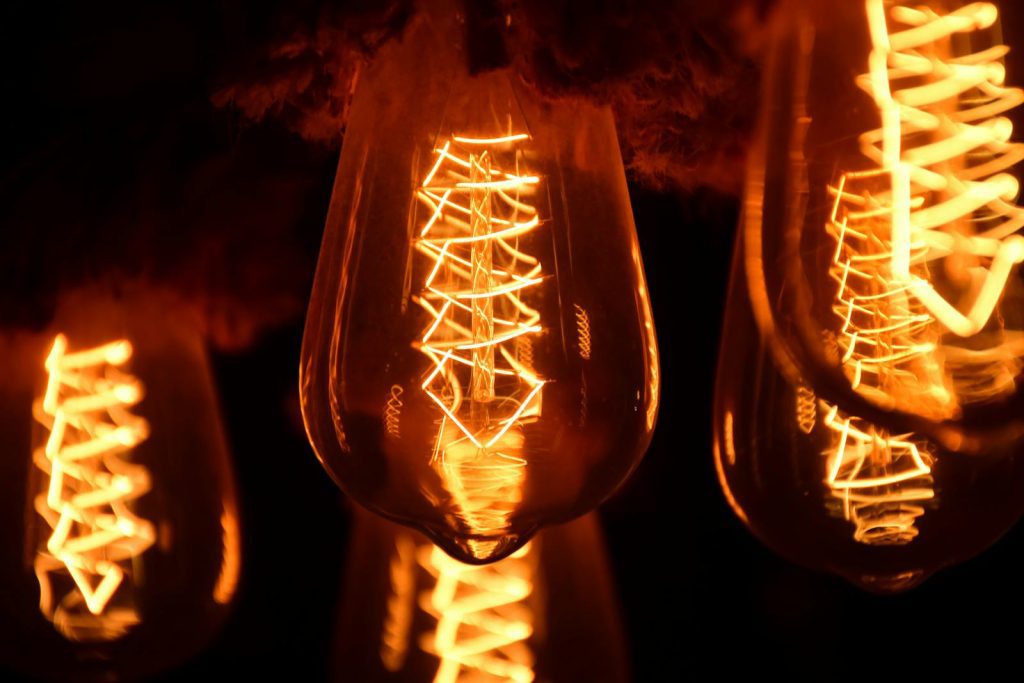

What separates incandescent bulbs from their solid-state rivals is not just how much power they draw, but how their light feels. The filament inside an incandescent lamp produces a smooth, full-spectrum glow that many people instinctively associate with comfort, intimacy, and rest. Research cited by lighting specialists notes that different color temperatures and spectral profiles can influence mood and alertness, and that the warm, continuous output of a filament can be especially appealing in homes and hospitality venues where relaxation is the goal. That is why some designers still specify incandescent or incandescent-like sources in restaurants, hotel lobbies, and living rooms, even when more efficient options are available.

Technical comparisons often focus on “Energy Efficiency and Longevity,” and it is true that incandescent bulbs fare poorly on both counts when stacked against LEDs. Yet even sources that emphasize those drawbacks acknowledge that, while they are often criticized for their energy use, incandescent lamps still offer a light quality that many users prefer in specific settings. That tension is captured in analyses that explain why Energy Efficiency and Longevity do not fully settle the debate, because the subjective experience of light can outweigh the objective savings on a utility bill, especially in spaces where bulbs are used only a few hours each evening.

Holiday lights show how nostalgia becomes infrastructure

The most visible front in the incandescent revival is seasonal, not everyday, lighting. Holiday displays have become a laboratory for how emotion, tradition, and aesthetics can override efficiency metrics. Even as programmable LED strings dominate big-box aisles, a significant share of households still seek out glass bulbs that look and behave like the ones they grew up with. Analysts describe this as “Nostalgia as Cultural Infrastructure,” a phrase that captures how family rituals and neighborhood expectations can lock in certain technologies long after they cease to be rational on paper. In this context, the warm, slightly uneven glow of a filament is part of the ritual itself, not just a technical choice.

Reports on why people keep buying older strings emphasize “The Unmatched Warmth and Light Quality” of incandescent Christmas bulbs, noting that their color rendering and gentle fade create a sense of depth that many LED products struggle to replicate. That emotional and visual pull helps explain why some households still use Why Do People Still Use Incandescent Christmas Bulbs Despite Inefficiency, even when they know they are paying more to power them. The bulbs become heirlooms, passed down and carefully repaired, and the extra cost is treated as part of the holiday budget rather than a mistake.

From vintage Christmas strings to premium Edison bulbs

Holiday nostalgia is not limited to one style of decoration. Vintage C9 and C7 strings, with their oversized glass shells and saturated colors, have seen a resurgence in online searches and marketplace listings. Commentators point out that, in an age of smart lighting and animated LED displays, these older designs offer a sense of stability and “symbolic continuity with past traditions” that newer products cannot easily match. The appeal is not just the look of the bulbs when lit, but the ritual of untangling, replacing, and carefully screwing in each lamp, a tactile experience that many people find grounding during an otherwise digital season.

That same appetite for tangible, visible filaments is driving interest in decorative Edison-style lamps for everyday use. Products like the Newhouse Lighting ST64INC-6 60-Watt Equivalent Vintage Style Edison Bulbs are marketed as a way to bring a warm, industrial aesthetic to kitchens, cafes, and home offices. Shoppers can Find out more about the product through detailed listings that highlight not only wattage and base type, but also filament shape and glass tint. In this segment, inefficiency is reframed as a feature, a sign that the bulb is “real” rather than simulated.

Data, algorithms, and the new incandescent shopper

The return of incandescent bulbs is also a story about how people shop. Instead of wandering hardware aisles, consumers now rely on search engines and recommendation systems that surface niche products based on behavior patterns. Platforms describe how their Shopping Graph connects “Product information aggregated from brands, stores, and other content providers” to build a constantly updated map of what is available and who might want it. That infrastructure makes it easier for a small but passionate audience to find exactly the incandescent style they prefer, from clear ST64 lamps to colored C9 strings, without depending on local inventory.

Within that ecosystem, specific listings, such as the Newhouse Lighting ST64INC-6 60-Watt Equivalent Vintage Style Edison Bulbs, can be discovered through multiple paths, including direct queries and algorithmic suggestions. A shopper who searches for “vintage filament” or “warm Edison bulb” might land on a page where they can again Find out more about the product, compare prices, and read reviews that often focus on glow, dimming behavior, and perceived coziness rather than kilowatt-hours. In that sense, data-driven retail is amplifying a niche preference into a visible trend, giving incandescent fans a louder voice than they might have had in a purely brick-and-mortar world.

Health concerns, emotional pull, and the limits of nostalgia

Not every incandescent buyer is chasing a memory. Some are motivated by discomfort with certain LED characteristics, especially in spaces where people spend long stretches of time. Commentators who frame the debate as a “Win for Market Competition and Your Health” argue that the spectral smoothness and lack of high-frequency flicker in traditional bulbs can be easier on the eyes for those prone to headaches or sleep disruption. They point to analyses like Why You Should Care, which link lighting choices to circadian rhythms and overall well-being, and argue that a one-size-fits-all efficiency mandate risks ignoring those nuances.

At the same time, holiday coverage makes clear that “The Emotional Pull of Traditio” is powerful in its own right. Analyses of why some people are switching back to older Christmas strings despite higher cost describe how the glow of a familiar bulb can anchor family rituals, even as smart speakers and streaming services transform other parts of domestic life. Reports on Why Are Some People Switching Back To Incandescent Christmas Bulbs Despite Higher Cost note that, no matter how advanced the technology becomes, a segment of users will pay more for the sensory and emotional continuity that incandescent light provides. That willingness complicates any simple narrative that efficiency alone will determine the future of lighting.

A century-old bulb and the meaning of durability

Perhaps the most striking symbol of incandescent resilience is not in a living room or on a front porch, but in a California fire station. The so-called “world’s oldest light bulb” has been glowing almost continuously for more than a century, long enough to become a minor tourist attraction with its own guest book and “official” website. Visitors marvel that a fragile-looking glass envelope has outlasted generations of firefighters, trucks, and building renovations, and the bulb has become a kind of mascot for the idea that older technologies can be surprisingly robust when treated gently and run at modest power.

Technical explanations for its longevity point to factors like low operating wattage and a carefully controlled power supply, conditions that are not typical of everyday household use. Still, the story resonates in an era when some smart light bulbs fail after only a few years, often because of electronics rather than the light source itself. Coverage of how the world’s oldest light bulb has stayed lit contrasts that century-long glow with the shorter lifespans of some smart products, underscoring that durability is not solely a function of newness. For consumers weighing what to screw into their next socket, that story is one more reminder that the future of light may be more plural, and more incandescent, than the efficiency charts once suggested.

Vintage bulbs in a smart, LED world

Even as LEDs and smart systems continue to dominate new construction and large-scale retrofits, incandescent bulbs are carving out a role as a premium, situational choice. Holiday coverage on Why Are Vintage Christmas Bulb Lights Becoming Popular Again notes that, in an age of smart lighting and programmable LED displays, the older technology offers a counterpoint that feels slower, more tactile, and more human. That same logic applies to dining rooms lit by exposed Edison filaments or reading nooks where a single warm bulb softens the edges of a long day spent in front of screens.

Behind the scenes, the infrastructure that supports this niche is thoroughly modern. Platforms that map “Product information aggregated from brands, stores, and other content providers” use tools like the Product information aggregated Shopping Graph to keep incandescent SKUs visible and searchable, even as their share of total sales remains modest. The result is a lighting landscape where hyper-efficient LEDs handle most of the heavy lifting, while incandescent bulbs, far from disappearing, reemerge as carefully chosen accents that speak to comfort, memory, and a desire for light that feels as good as it looks.

More from Decluttering Mom: