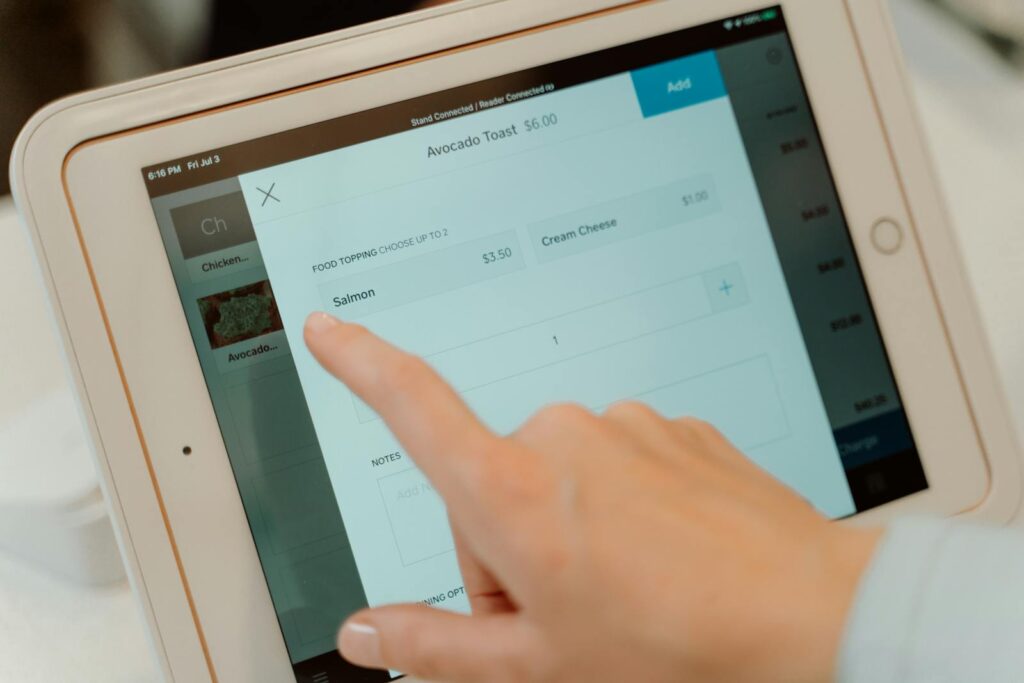

Self-checkout was supposed to be the future of fast, frictionless shopping. Instead, it has turned into one of retail’s biggest headaches, with theft spiking just as major chains quietly rip out the very machines they once rushed to install. As stores like Walmart and Dollar General scale back the kiosks, they are exposing a deeper tension between convenience, cost cutting, and basic trust at the checkout lane.

What is unfolding now is not a minor tweak in store layout but a broad reset of how Americans pay for everyday goods. Retailers are discovering that the savings from fewer cashiers can be wiped out by “shrink,” the industry’s catchall for missing merchandise, and that a surprising number of shoppers are willing to treat self-checkout as a gray zone for stealing.

The quiet retreat from a once unstoppable technology

For years, big-box chains treated self-service lanes as a no-brainer, a way to move more people through the front end with fewer employees on the clock. That logic is now colliding with reality as companies like Walmart roll back self-checkout in key stores after a surge in theft and mounting pressure over losses. Internal pilots have shifted lanes back to staffed registers, a sharp turn for a retailer that once leaned hard into automation at the front end.

The pullback is not limited to one chain. Reporting on how Walmart is not alone underscores that the industry follows Walmart’s lead when it comes to store formats and technology. As shrink eats into margins, that leadership now looks like a U-turn, with other chains reassessing whether the machines that once symbolized modern retail are worth the trouble.

Dollar General’s about-face shows how fast the tide turned

If Walmart signaled the direction of travel, Dollar General slammed on the brakes. The discount chain, which operates thousands of small-box stores in rural and low income communities, initially embraced self-checkout as a way to keep labor costs lean. Then, in Mar, executives acknowledged that the experiment had gone too far and began stripping out kiosks in locations where losses were worst.

The shift has been sweeping. The company first said it would remove self-checkout from 300 of its highest theft stores, then later confirmed that self-checkout had been eliminated at about 12,000 locations, a majority of its footprint. The retailer framed the move as part of a broader strategy to combat shrink, a message echoed in separate coverage of how Mar decisions to pull kiosks from “high shrink” stores.

Self-checkout theft is not a rounding error anymore

Behind these reversals is a simple, uncomfortable fact: a lot of people are stealing at the machines, and many of them plan to keep doing it. New LendingTree research cited in multiple local reports found that 27% of self-checkout users have intentionally taken an item without scanning it, a figure highlighted in coverage of how New data suggests self-checkout theft has climbed over the last few years. That is not a fringe behavior, it is more than one in four users treating the lane as optional when it comes to paying.

The same research drilled into repeat behavior and found something even more alarming for retailers. According to LendingTree, “55 percent who have stolen at self-checkout said they will do it again,” a line repeated in a separate piece that also quoted “55 percent” as the key metric. That kind of repeat intent turns what might look like petty shoplifting into a structural problem for chains that process millions of self-checkout transactions a week.

Billions Lost to Theft and the math behind the U-turn

Retail executives are not just reacting to bad vibes at the front end, they are staring at spreadsheets that show billions of dollars evaporating. One analysis of the “Billions Lost” to shrink noted that major Retailers have been forced to reconsider self-checkout technology as theft rates soar, with the financial stakes described as high enough that security and service are now paramount. The same reporting said theft was a primary reason for trimming self-checkouts at 9,000 store locations, a scale that shows how widespread the rethink has become.

For a company the size of Walmart, even small percentage changes in shrink translate into eye watering sums. A legal analysis of “The Walmart Problem” pointed out that for a company as large as Walmart, with U.S. revenues around “$400 billion,” a 1 to 2 percent increase in shrink translates to billions of dollars in lost goods. That kind of exposure makes the cost of hiring more cashiers or redesigning checkout systems look like a bargain.

How much of the front end is actually self-checkout?

Part of what makes this moment so fraught is how deeply self-checkout has already been woven into the grocery and big-box experience. Research on Self Checkout Adoption and Theft Statistics found that “40%” of grocery store registers in the U.S. are now self-checkout kiosks, and that “43%” of shoppers prefer using them. Those numbers, attributed to “Self Checkout Adoption & Theft Statistics” and “Nearly 40%” in the research summary, show that any retreat from kiosks will be felt by a large share of customers who have built their routines around scanning their own carts.

At the same time, the same research flagged that stores with more self-checkout lanes can be less likely to be robbed in the traditional sense, even as they struggle with smaller, more frequent losses at the scanner. That nuance helps explain why some chains are not scrapping the technology outright but instead tweaking how it is used, a strategy echoed in guidance that “Rather than eliminating the lanes altogether, savvy retailers are fighting theft by reducing reliance on self-checkout or boosting staff in favor of more staffed checkout stations.” The result is a patchwork of approaches that vary by chain, city, and even individual store.

Shrewsbury’s 64% crime drop became a national talking point

Nothing has crystallized the debate quite like what happened in one Missouri suburb. In April 2024, managers at the Shrewsbury Walmart made the unusual decision to remove self-checkout entirely and rely on human cashiers, a move detailed in coverage of how In April the Shrewsbury Walmart pulled the plug on “smart” technology. The result was dramatic: reports say the store saw a “64%” drop in crime after removing the technology.

That local experiment quickly became a case study for executives and city officials elsewhere. Separate reporting on “Police Pressure and Local Strain” described how, in some cities, the problem of theft at big-box stores had become impossible to ignore, with In Shrewsbury, Missouri, the strain on local law enforcement was a key factor in pushing the store to change course. When a single operational tweak produces a 64% crime drop and eases pressure on police, it is no surprise that other communities are asking whether the convenience of scanning your own groceries is worth the cost.

Dollar General’s “staff first” pivot and what it signals

While Walmart has been experimenting store by store, Dollar General has been more explicit about what it wants customers to do. The company said its new setup “is intended to drive traffic first to our staffed registers, with assisted checkout options available as second or third options,” a line quoted in coverage of how the chain is changing its front end. That same report noted that self-checkout purchases in the chain’s stores had been linked to issues that “can include theft and shoplifting,” a blunt acknowledgment of why the pivot is happening, and it framed the changes as affecting hundreds of store locations across the country, including those highlighted on the main Dollar General site.

That “staff first” language, reported in detail in a piece on how Dollar General is getting rid of self-checkout in hundreds of stores, is a sharp contrast to the earlier era when chains nudged shoppers toward kiosks with signage and staffing patterns that made human lanes feel slower. Now, the message is flipped: talk to a person first, use the machine only if you really want to. It is a cultural reset as much as a technical one.

Customers are split between speed and trust

For shoppers, the retreat from self-checkout is landing in a landscape already shaped by frustration over locked cases and security guards at the end of every aisle. Coverage of how more Rite Aid stores in Southern California are locking up items described how, “As the smash-and-grab trend plagued business across Los Angeles, more big retailers are stepping up security to keep their merchandise safe.” That same “As the” description captures the mood in many cities, where shoppers now navigate a maze of plexiglass, alarms, and cameras just to buy toothpaste.

At the same time, a viral clip titled “Video Transcript When has to guard cucumbers, you know it is bad” captured the absurdity of the moment, as a narrator described how Walmart is ditching self-checkouts in key stores and bringing human cashiers back to restore trust and real customer connection. That video framed the shift as a reminder that convenience has its limits, a sentiment that resonates with shoppers who say face-to-face service feels safer and more reliable, even if it sometimes means waiting in a longer line.

Where retailers go from here

Despite the high profile retreats, self-checkout is not disappearing overnight. Some chains are trimming lanes rather than ripping them out, others are experimenting with hybrid models where staff hover near kiosks to help and to deter theft. Industry guidance that “Rather than eliminating the lanes altogether, savvy retailers are fighting theft by reducing reliance on self-checkout or boosting staff in favor of more staffed checkout stations” captures the middle path many are trying to walk, a path that still leans on automation but no longer treats it as a cure all.

What is clear is that the era of unchecked expansion is over. Reporting on how Self-checkout theft is on the rise as Walmart and Dollar General quietly remove machines, and on how Self-checkout theft is not as warm as you think, has made it harder for chains to pretend that shrink is just the cost of doing business. As Walmart, Dollar General, and others recalibrate, the checkout lane is turning into a test of how far retailers can push automation before customers, communities, and their own balance sheets push back.

More from Decluttering Mom: